When Leibniz came to Paris in 1672, his mathematical knowledge was rather scant. It was through his acquaintance with Ch. Huygens, one of the leading mathematicians of his time in Europe, that Leibniz’s interest in Mathematics sparked. One of the problems that Huygens proposed was that of finding the sum of the series of the reciprocals of triangular numbers

Realizing that the terms in the series were the successive differences between the terms of the sequence

Leibniz concluded that the th partial sums of the former sequence were equal to the difference between the

-th term and the first term of the latter, that is

(this device is what we call telescoping). He developed this idea, considering sequences of differences of differences (second differences), third differences, etc. Thus, one can move “up” and “down” along the sequence of successive differences, establishing relations between the sums of differences and the net change of the generating sequence.

Perhaps the simplest example is that of arithmetic sequences . In this case, the sequence of differences is constant,

. The sum of the first

differences is just

hence

or

. Arithmetic sequences are just linear functions of

.

Now, what if the differences of the original sequence form an arithmetic sequence and the second differences are constant?

Suppose the original sequence is , the sequence of first differences is

where

and the sequence of second differences is

with

, a constant. We know that

is an arithmetic sequence with difference

, hence

. Hence

,

Adding all the relations above and taking into account the cancelations on the left hand side (telescopic effect) we obtain

or

Observe the following: a) is given by a second degree polynomial; b) the free term is the first element of the sequence

, the coefficient of the linear term is

, the first “first difference”, and the coefficient of the quadratic part is

, which is the constant value of the second difference. At this point it should be clear that we can extend this procedure to the case when the third differences or, more generally, the differences of a certain order

are constant. Unsurprisingly, we get polynomials of degree equal to the order of the constant difference, where the coefficients only depend on the first values of consecutive differences. This is what we could call a “discrete” (and finite) Taylor series.

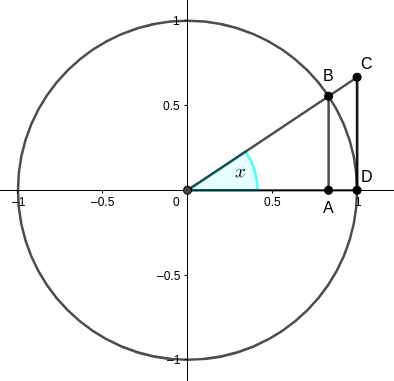

Leibniz was, above all, a philosopher. He realized that he could extend this methods to functions of a continuous variable. But then he would have to replace the differences by infinitesimal differences between to “successive” values of the variable. He had been thinking about the concept of infinitesimal for years, particularly through correspondence with Hobbes and his concept of “conatus“. All the pieces came together in his mind, leading to the creation of infinitesimal Calculus within a few years. Simultaneously, he introduced the notation for successive “differentials”: etc. and integrals (“summa omnia”)

for the above processes of moving “down” and “up”, but this time applied to functions of a continuous variable. The passage

becomes

. We deal with the continuous case in the next post.