In simple instances, tangency can be easily characterized. For example, a straight line is tangent to a circle precisely when they share a unique point. More generally, a curve which is the smooth boundary of a convex set has a unique tangent at each point, which can be characterized as the supporting line of the convex set.

But in more general cases such description is inadequate. For example, how do we characterize the tangent to the graph of a polynomial like at the point

? The epigraph is not convex, so the description as a supporting line is not available. Also, it clearly intersects the graph at some other point. Even worse, at the point

the tangent actually crosses the graph, so the latter is not contained in either one of the two half-planes defined by the tangent, even locally. For polynomials, an algebraic definition of tangency in terms of the multiplicity of the point of tangency as a root to a polynomial equation is available, but in more general situations an analytic description is needed.

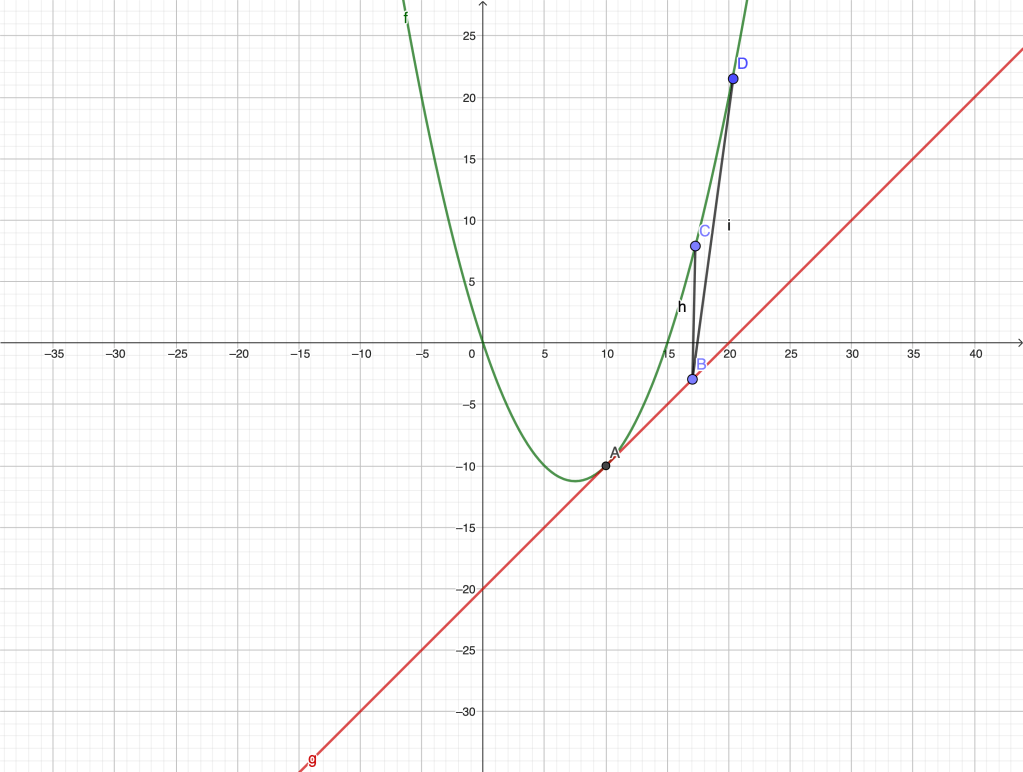

Finding tangents, along with finding areas, is one of the geometric problems that gave impetus to the use of infinitesimals and the eventual creation of Calculus. Predecessors of Newton and Leibniz, notably Fermat and Descartes, devised methods for finding tangents. For example, according to Fermat’s method, to find the tangent to the graph below at , he would choose a point

on the graph, very close to

, and would argue that the triangles

and

were “almost” similar. He then wrote an “adequality” (approximate proportion)

or, calling (the subtangent)

.

This, in turn, can be written as

.

Expanding and simplifying the left hand side and setting (a predecessor of “finding the derivative”) gives

,

being the slope of the tangent. When

is a polynomial function of

, this program can be easily carried out.

These ideas were further refined by Roverbal, Wallis, Barrow, Newton and Leibniz. The latter defined the tangent as the line through a pair of infinitely close points on the curve.

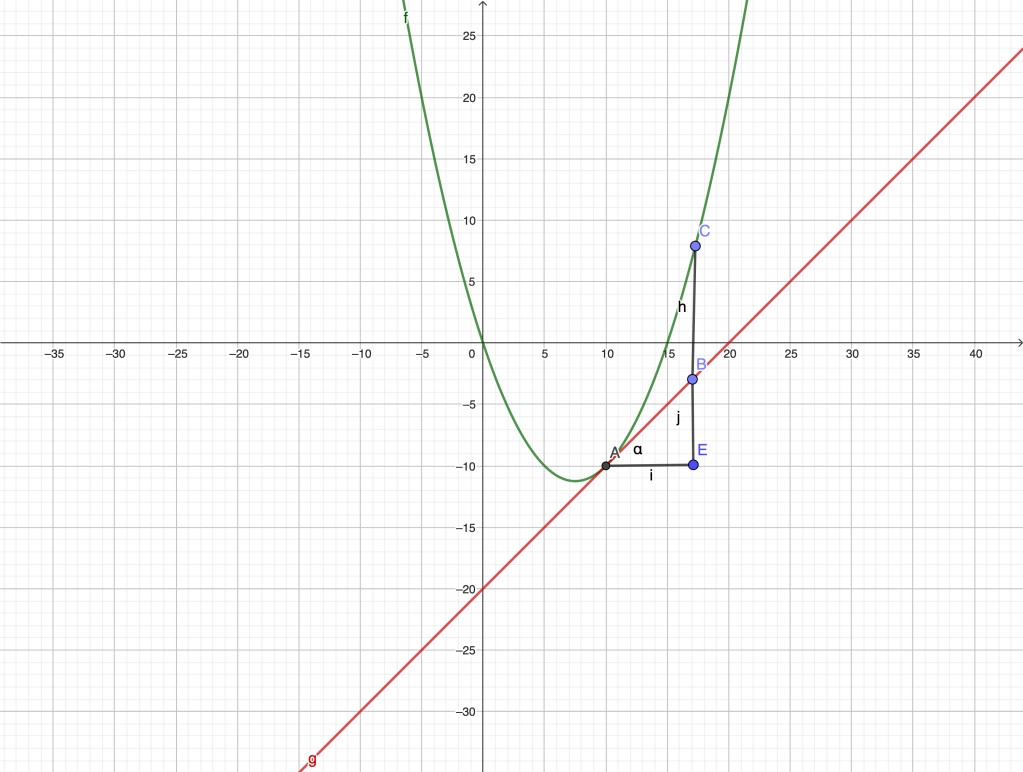

The modern analytic characterization is the following: the tangent line at a point of a curve has to be such that, as we move along the tangent towards the point of intersection with the curve, the distance to the graph in any “transversal” direction decreases to zero faster than the distance “along” the tangent to the point of intersection. That is, the curve is “transversally” closer to the tangent near the given point. In a sense, the neglect of the transversal separation between the triangles and

is the key to Fermat’s construction. The following figure clarifies the situation further.

The line is tangent to the graph at

if

when is infinitesimal. The transversal direction chosen is irrelevant. Had we chosen the direction

in the above figure, we would still have

, since as

approaches

, the curve and the tangent become “parallel” and the ratio

stabilizes to some positive constant.

Notice that, for a non-tangent, transversal line through , the ratio

is not infinitesimal, but rather stabilizes to a positive value depending on the final non-zero angle between the curve and the chosen non-tangent line.

It follows from our definition that the tangent is unique (if there is one). It is also worth noting that the concept of tangency belongs to Euclidean, as well as to affine geometries: tangency does not break down under rigid motions, translations and more general affine transformations (shear, dilations, etc.)

It is natural to quantify the “amount” of tangency by the order of the infinitesimal with respect to

. Namely, we will say that the order of tangency is

if

So, in particular, the order of tangency is zero if the line is transversal to the curve, it is one if is a quadratic infinitesimal, etc. The order of tangency may not be an integer.

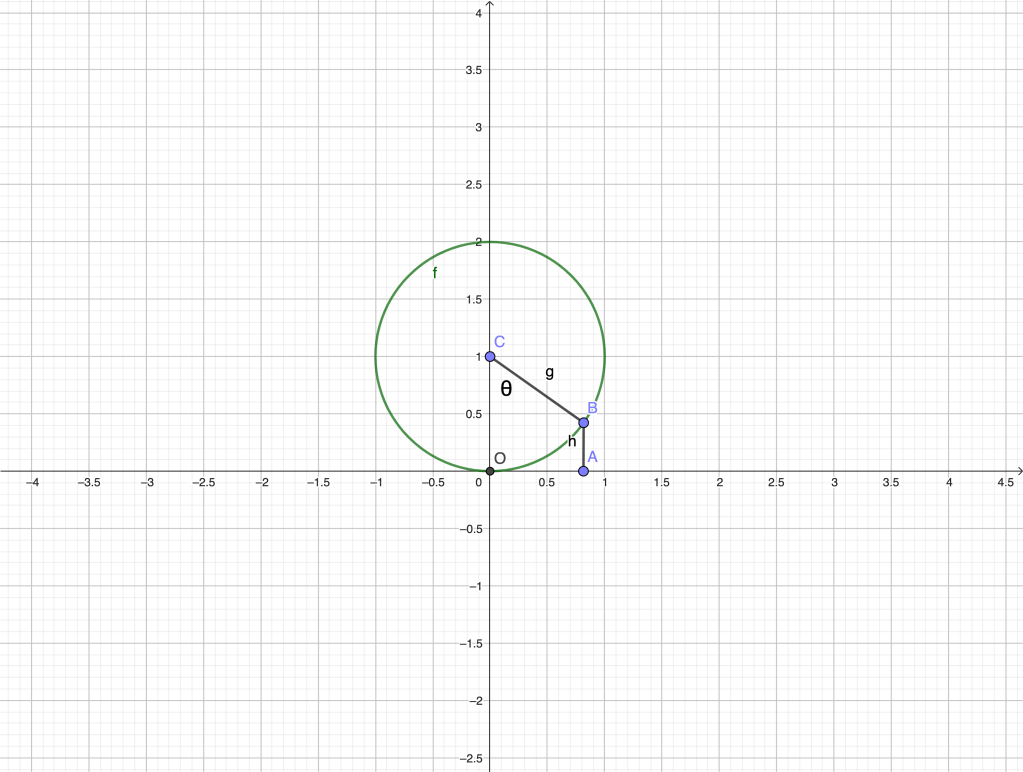

Tangents and differentiability

The existence of the tangent to the curve at a point

is intimately related to the existence of the first differential

. To see why, we start by noticing that if the curve

has a non-vertical tangent at

(see figure below), the vertical distance between the graph and the tangent is also infinitesimal with respect to

, because

and

are proportional,

. Therefore

when is infinitesimal. But

, where

is the abscissa of the moving point

.

If we assume that the straight line is tangent at

, we should have

or

.

But this is precisely our definition of differentiable function at , with

. Therefore, the existence of a tangent with slope

implies differentiability with

. The value of the derivative is the slope of the tangent.

If the order of tangency is , that is if

,

it follows from the definition that for

.

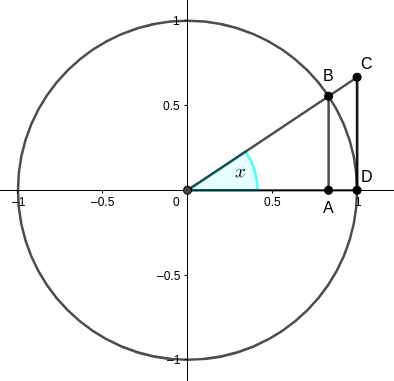

As an example, let’s examine the order of tangency between a circle and its tangent at some point. For simplicity, consider the circle

with unit radius, center and tangent to the

-axis at the origin

, see the figure below.

We have ,

. Therefore,

as . Hence

. Actually,

is an infinitesimal of the second order with respect to

. Indeed,

as . Thus

and the order of tangency is

.

The value of the limit would be different for circles of different radii. Indeed, if our circle was

, since the numerator and denominator in

scale differently, the limit would be

.

The usual (linear) angle between a circle and its tangent at one point is zero. But our previous analysis allows to quantify the separation between the circle and the tangent using an infinitesimal quadratic scale. Observe that when is close to zero,

is very large, whereas when

is very large and the circle is “very close” to its tangent,

is close to zero.

Angles like the above, whose usual measure is zero but their extent can be quantified as before, have been known since antiquity.

Horn angles

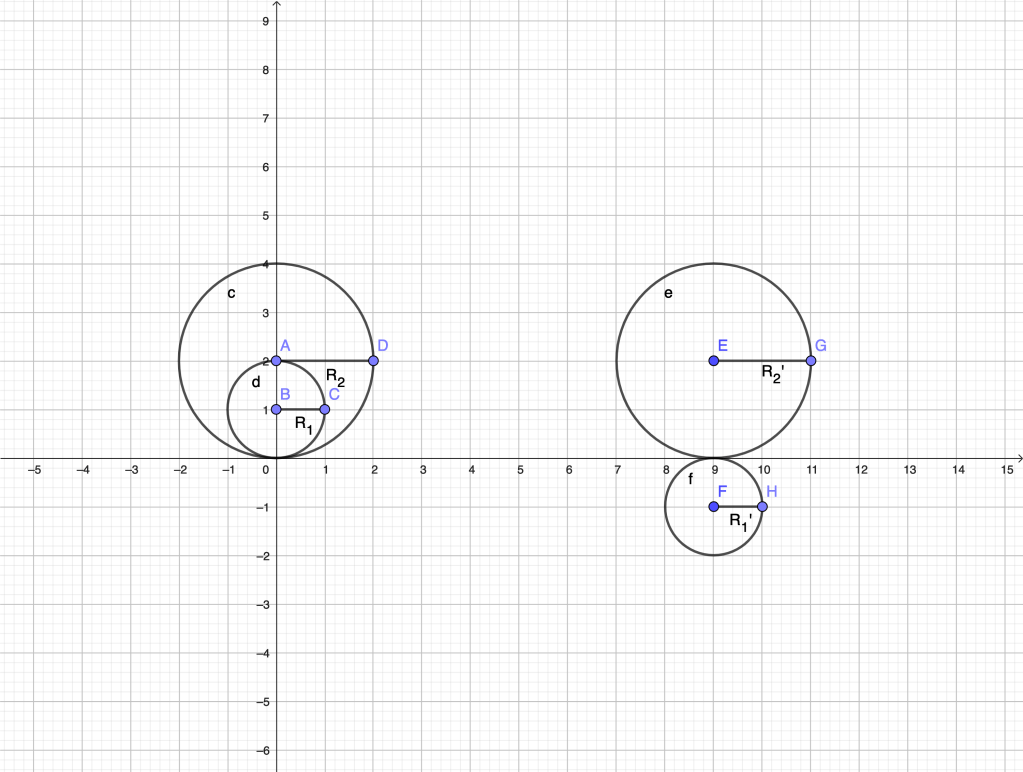

A horn angle is the angle formed between a circle and its tangent or, more generally, between two tangent circles at their point of tangency. Given two circles internally tangent, it is natural to define the measure of the horn angle between them as the difference of the angles they form with their common tangent. If they are externally tangent, we take the sum instead, as in the figure below.

Thus, in the first case,

in the second. The factor

is common and omitted for simplicity. For a circle of radius

, the quantity

is called its (scalar) curvature. The measure of a horn angle between two tangent circles is the difference/sum of their curvatures.

Horn angles are mentioned by Euclid in Book III (Prop. 16) of the “Elements”, and were known to Archimedes and Eudoxus. Euclid states that a horn angle is “smaller than any acute angle”. That property made horn angles problematic to Ancient Greek mathematicians, since they always assumed that any two “homogeneous” magnitudes (lengths, angles, areas, ..) were comparable, in the sense that anthyphairesis (as we would say today, the Euclidean algorithm) could be applied to them. At the end of the process, commensurable magnitudes could be assigned numbers with respect to some unit. Incommensurable magnitudes could not, but the situation could be handled by means of Eudoxus’ theory of proportions, a predecessor of Dedekind’s theory of real numbers. But the notion of a non-zero angle smaller than any acute angle was out of grasp. In modern terminology, we would say that the Archimedean property of segments, angles, areas was a basic assumption in Greek geometry.

We have been able to define a measure for horn angles using the concept of order of infinitesimals. However, to restore the Greeks’ assumption on the possibility to compare (albeit “in the limit”) any pair of angles, actual infinitesimal angles of different orders need to be included in the picture. This is the content of non-Archimedean Geometry, based on the construction of non-Archimedean fields (surreal, hyperreal numbers) in Nonstandard Analysis. The development of these ideas is a very interesting chapter of Analysis, well deserving a separate post, or even a separate thread.