The structure of the real line is deceptively intricate. Rational and irrational numbers are densely interwoven, yet they differ fundamentally—not just in their arithmetic properties, but in how they can be approximated. Even the rationals themselves possess a rich, hierarchical organization, elegantly captured by the Stern-Brocot tree.

If you take a course on Real Analysis where these matters are looked at in some detail, or an Algebra course where extensions of the rational field are considered (say, a course on Galois theory), you encounter the concepts of algebraic and transcendental numbers. Rational numbers can be thought as the ones solving a linear equation

with integer coefficients,

. A natural generalization leads us to the definition of algebraic numbers as real numbers satisfying a polynomial equation of the form

with integer coefficients

. The degree of an algebraic number is the lowest degree of a polynomial with integer coefficients having the given number as a root. Such polynomial has to be irreducible in

, otherwise the said number would be a root of a lower degree polynomial. Real numbers which are not algebraic are called transcendental. Clearly, all rational numbers are algebraic, and all transcendental numbers are irrational.

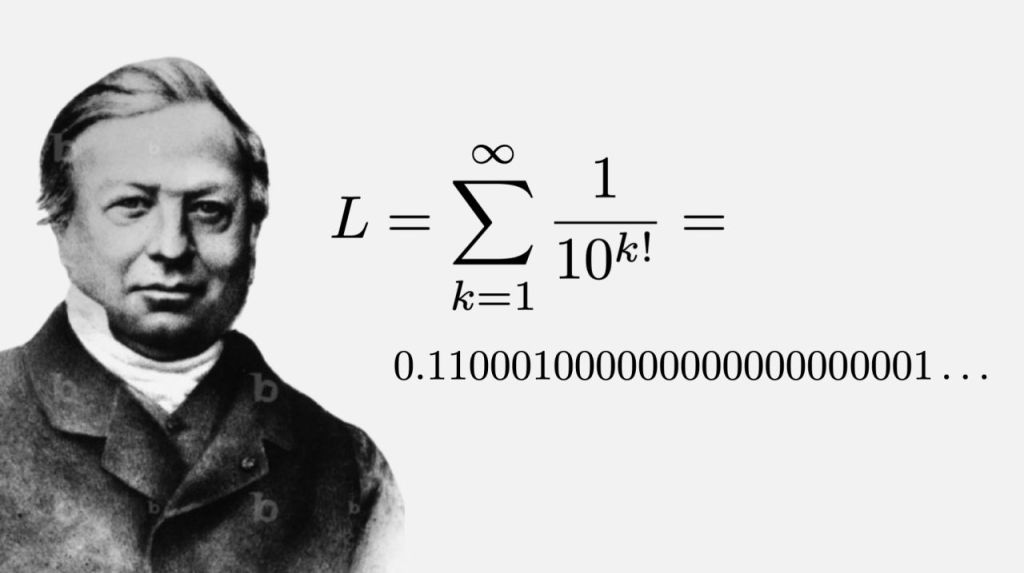

The idea of the existence of transcendental numbers goes back to Leibniz, but the first to prove it, by giving a concrete example, was J. Liouville in papers from 1844 and 1851, [1] & [2]. It is often the case that when transcendental numbers are presented, the examples provided include ,

, and the Euler-Mascheroni constant

or Apéry’s constant

are mentioned as candidates (it is not even known if those are irrational). Proving that

or

are transcendental was accomplished by Hermite and Lindemann in the second half of the XIX century, and their proofs are far from elementary and can hardly be motivated and put in simple terms.

In contrast, Liouville’s constant has a very simple structure and the proof of its transcendency is completely elementary. It is defined as the number

,

that is, the number where the “ones” appear at positions given by the factorials,

after the decimal point. Not being periodic,

is clearly irrational.

Here is the reason why is transcendental: it can be approximated “too well” by the partial sums of the series, contradicting a result proved by Liouville, whose (very simple) proof is given below. The statement of the result, which we accept for the time being, is as follows.

Theorem [1] : Let be an irrational algebraic number of degree

(i.e.,

is a root of an irreducible polynomial of degree

with integer coefficients). Then there exists a constant

such that for all rational numbers

(with

) we have

.

(in words, algebraic numbers are not “too close” to rationals, in the sense that the rate of convergence of sequences of rationals with increasing denominators is limited by the degree of the given algebraic number). Formula should be contrasted with the well known fact that the continued fraction convergents

of any irrational number

satisfy

.

Liouville’s constant violates the theorem

The partial sums are rational numbers with denominator

. It is clear that

On the other hand, if were algebraic of degree

, we would have, according to Liouville’s Theorem,

But relations and

clearly contradict each other for large

. Indeed, for large enough

, we have

,

since . Thus,

is transcendental.

A proof of Liouville’s Theorem

Proof: By definition, there exists an irreducible polynomial in

with . If

is a rational number in lowest terms (

, then

is a non-zero integer,

and therefore

.

Next, we relate to

via the Mean Value Theorem,

for some between

and

. If we fix an interval around

, that is, if we assume, say,

, then

and the previous estimate entails

.

The assertion follows with .

Final Remarks

During the time of Liouville and Hermite, transcendental numbers appeared rare and exotic, requiring ingenious proofs to isolate even a handful of examples. Yet just a few decades later, in 1874, Cantor demonstrated that, in fact, almost all real numbers are transcendental. What seemed like a hunt for “needles in a haystack” turned out to be a realization that the “haystack” was almost entirely made of “needles.” His proof, however, was non-constructive—relying not on explicit examples but on the abstract principles of cardinality and the countability of algebraic numbers.

Here is a question worth pondering: If almost all numbers are transcendental, why do the ones we encounter so rarely reflect that? Part of the answer to this question is probably that humans think algorithmically. We are drawn to numbers we can compute, describe, or construct. Most numbers are not describable.

The apparent simplicity of Liouville’s constant is deceptive—a trick of human intuition. What makes it seem simple is merely the ease of describing its decimal representation. By contrast, a number like might appear ‘chaotic’ in its decimal expansion, yet it is fundamentally structured: as a quadratic irrational, its continued fraction is perfectly periodic,

.

The same applies, for instance, to the golden ratio, again a quadratic irrational with a very simple continued fraction representation, etc. This reveals a deeper truth: our perception of mathematical simplicity often depends on the representation we choose, not the object itself.

I hope you enjoyed this dive into Liouville’s constant — its deceptively tidy decimal mask is, after all, a very human kind of charm.

Bibliography

[1] Liouville, J. (1844), “Mémoires et communications”. Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Sciences (in French). 18 (20, 21): 883–885, 910–911.

[2] Liouville, J. (1851), “Sur des classes très étendues de quantités dont la valeur n’est ni algébrique, ni même réductible à des irrationnelles algébriques”, Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées, 16, 133–142. https://www.numdam.org/item/JMPA_1851_1_16__133_0.pdf