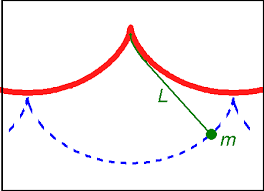

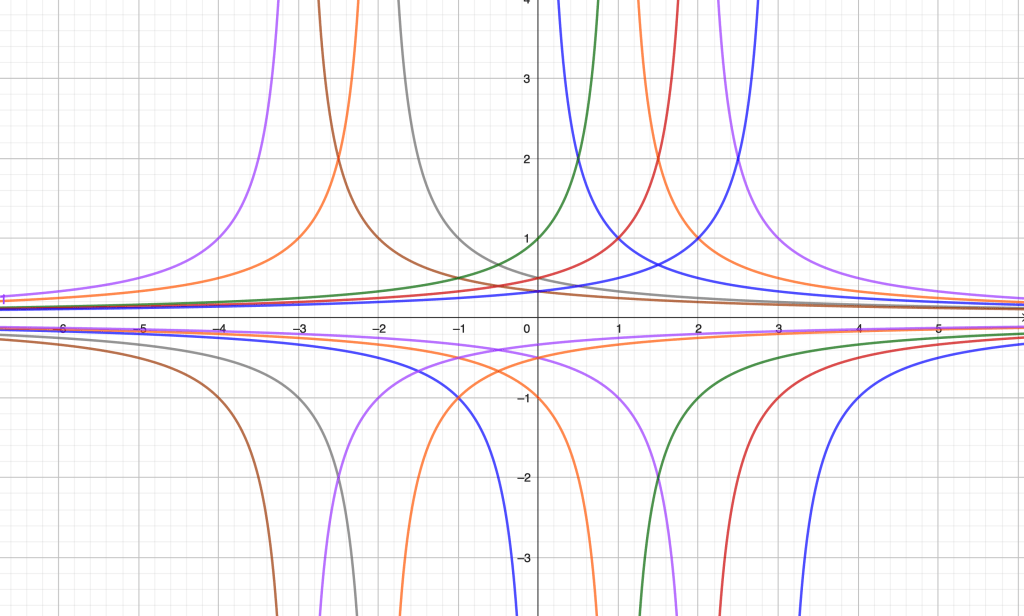

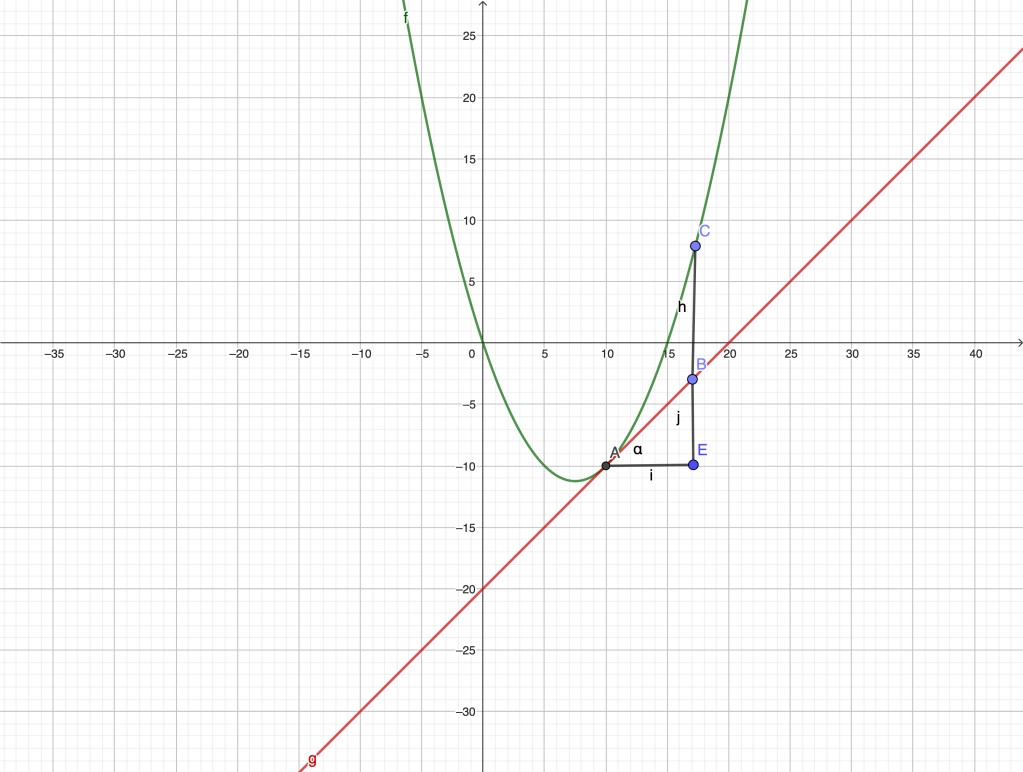

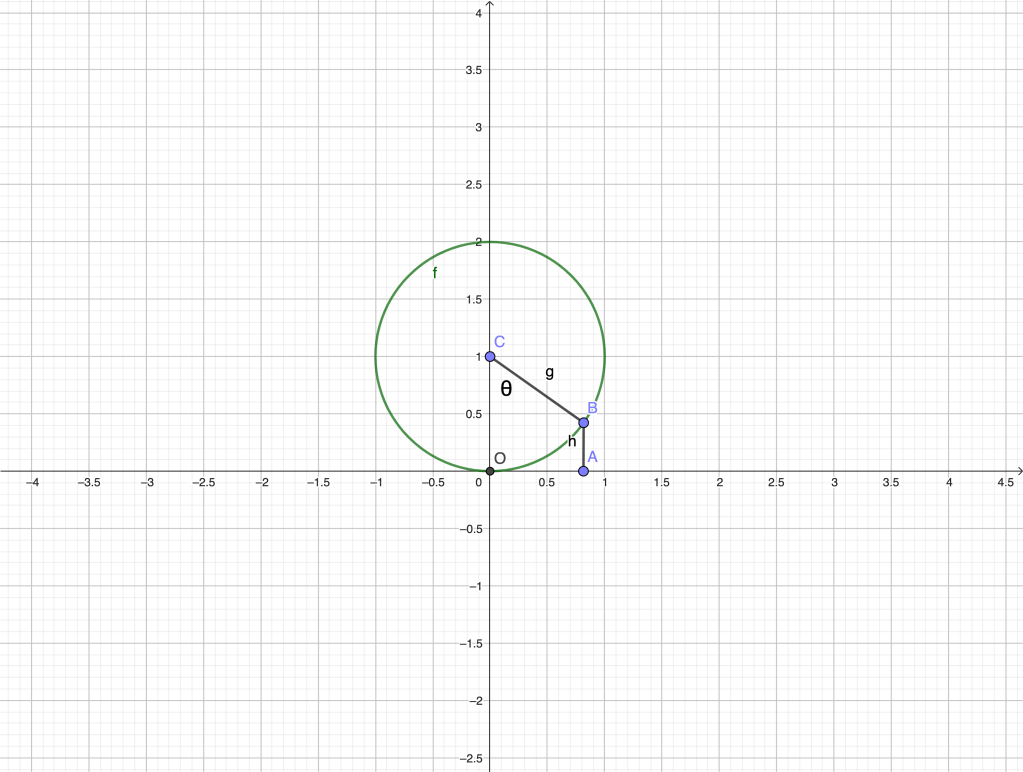

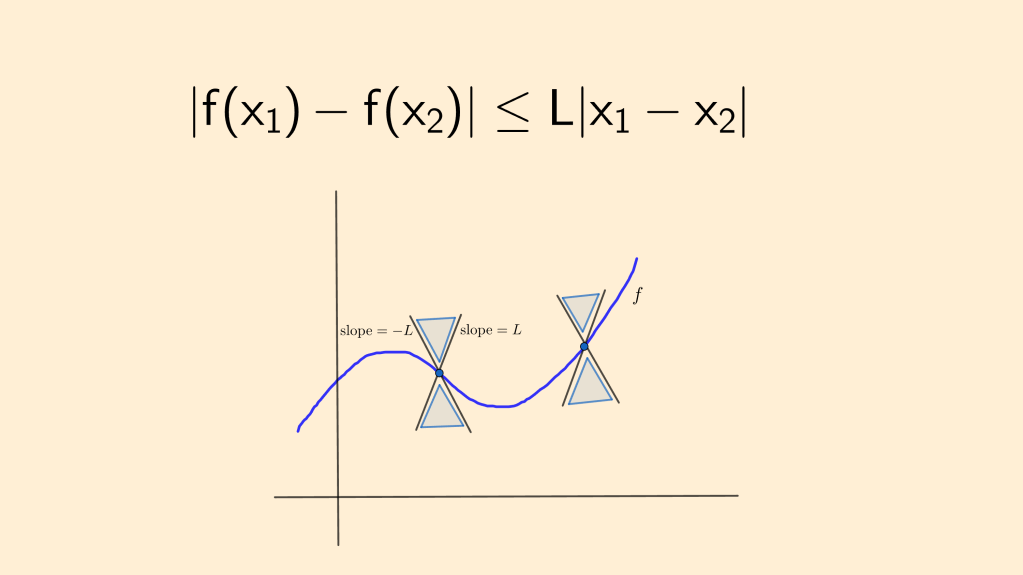

Fig.1. (L) The Lipschitz condition for a function . (R) Rudolph Lipschitz (1832 -1903)

A classic condition on the right hand side of a first order normal ODE

guaranteeing local uniqueness of solutions with given initial value is Lipschitz continuity of

in the

variable in some open, connected neighborhood

of

where

is defined. That is, it is required that there exist some constant

such that

for all in

. Under the above condition there is a unique local solution of the initial value problem

where uniqueness means that two prospective solutions defined on open intervals containing coincide in their intersection. We assume that our solutions are classical,

, continuously differentiable. Such solutions exist when extra conditions on

are imposed. For instance, if

is assumed continuous in

, classical local solutions exist and can be extended up to the boundary of

. But here our concern is uniqueness.

My goal here is to explain why such condition implies uniqueness in simple terms, how it can be generalized and the relation between uniqueness and another interesting phenomenon, namely finite-time blow-up of solutions.

To illustrate the idea, we will assume that and

. We will also assume that

for every

and, therefore, one solution of the above IVP is

. The general case reduces to this one, as we explain later.

We focus on forward uniqueness. Namely, we will prove that a solution with

for some

can never be zero at

. We will assume

, as the case

can be handled in a similar way. Backwards uniqueness also follows easily from the forward result.

Uniqueness is violated if, as decreases from

to zero,

vanishes at some point

,

, while

for

. By the Lipschitz condition,

while . It then follows from the ODE that

along the solution for . Integrating this inequality over

,

This integral inequality is the crux of the argument. Just observe that, since the improper integral is divergent, approaching zero would require

, contradicting the assumption

as

. The Lipschitz condition prevents

from becoming zero over finite

-intervals.

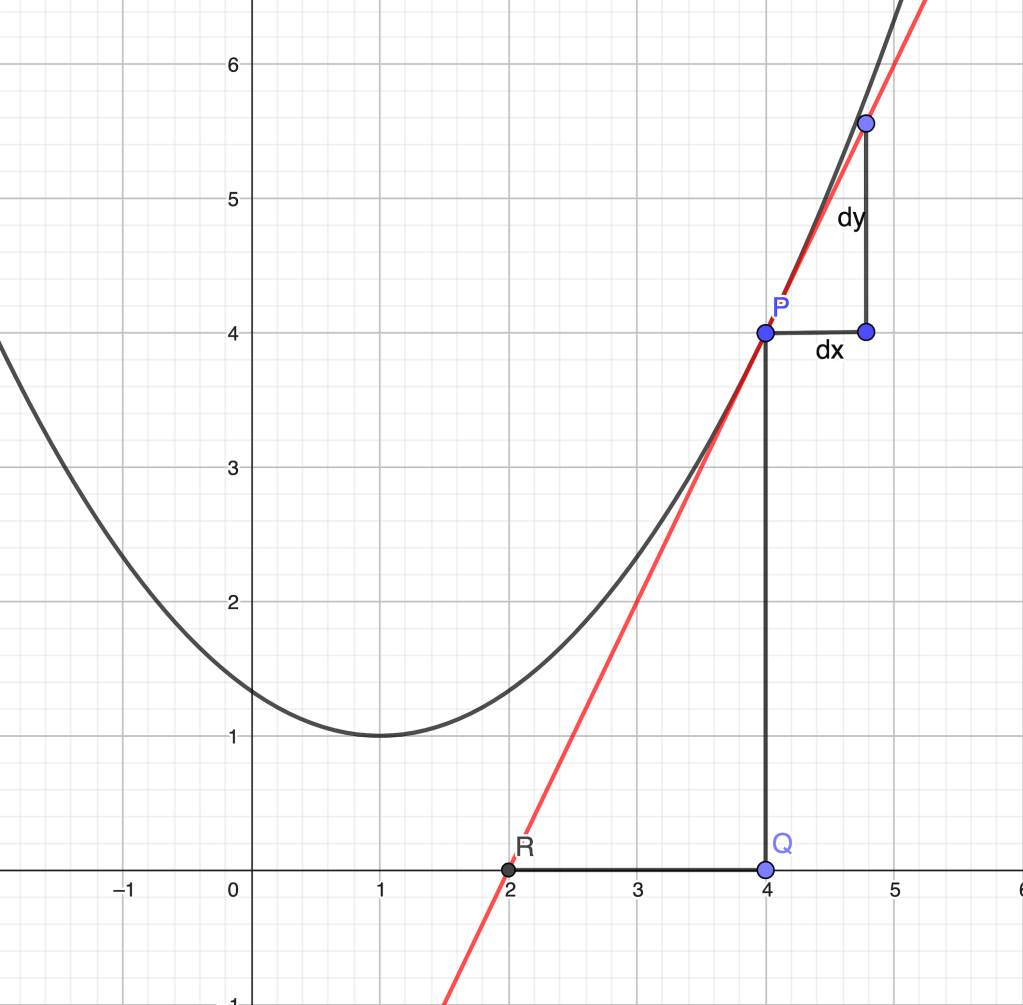

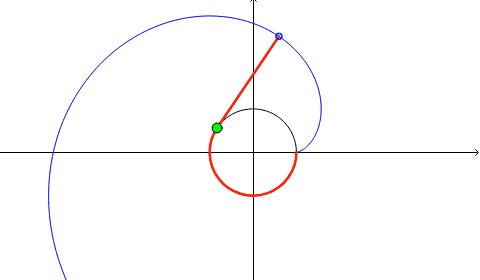

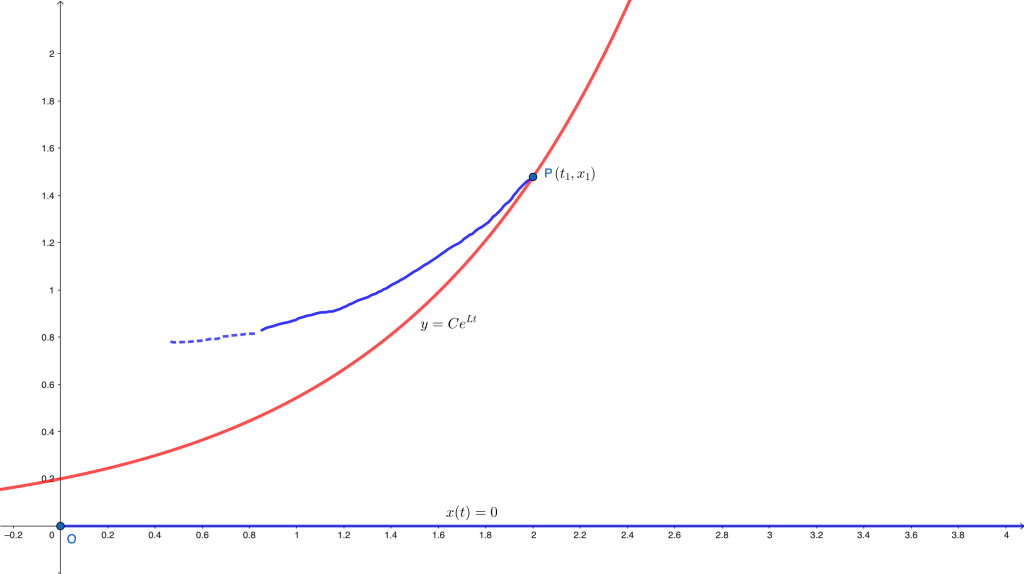

The argument above is equivalent to the following: for any solution with

for some

one can construct an exponential barrier from below of the form

for some

, that is,

for all

in its domain, thus preventing

from becoming zero. Indeed, the inequality

implies that our solution is increasing at a slower pace than the solution

of the IVP

which is nothing but for the appropriate

. Therefore,

to the left of

. In other words,

acts as a lower barrier for

, as in the figure below.

Fig 2. The exponential barrier prevents the solution through from reaching the

-axis.

If we assume that , we use the inequality (again a consequence of

)

for to conclude that

with

is a barrier from above for our solution, preventing it from reaching the

-axis.

The integral inequality suggests a very natural generalization. Indeed, all we need is a diverging (at zero) improper integral on the right-hand side. We can replace the Lipschitz condition by the existence of a modulus of continuity, that is a continuous function

with

,

for

satisfying

in , with the additional property

.

This more general statement is due to W. Osgood. The Lipschitz condition corresponds to the choice . The proof is identical to the one above, given that the only property we need is the divergence of the improper integral of

at

.

Thus, for an alternative solution to branch out from the trivial one, we require a non-Lipschitz right-hand side in that leads to a convergent improper integral. This condition is satisfied, for instance, in the autonomous problem

which, apart from the trivial solution, has solutions of the form on

and

for

for any

.

There is nothing special about the power in this example. Any power

with

would do. These examples of non-uniqueness are usually attributed to G. Peano.

Uniqueness for general solutions can be easily reduced to the special case above. Namely, if and

are local solutions of

(say on

), then

is a local solution of

on with

. Moreover,

satisfies a Lipschitz condition near

if

does near

, with the same constant

. By the above particular result,

and hence

on the corresponding intervals.

Remarks: A simple and widely used sufficient condition for

to hold is the continuity of the partial derivative

in an

-convex region

(typically a rectangle). This follows from a straightforward application of Lagrange’s mean value theorem;

is not necessary for uniqueness, as the example of

with

with

shows;

The Lipschitz condition is relevant in other areas of Analysis. For instance, it guarantees the uniform convergence of Fourier series.

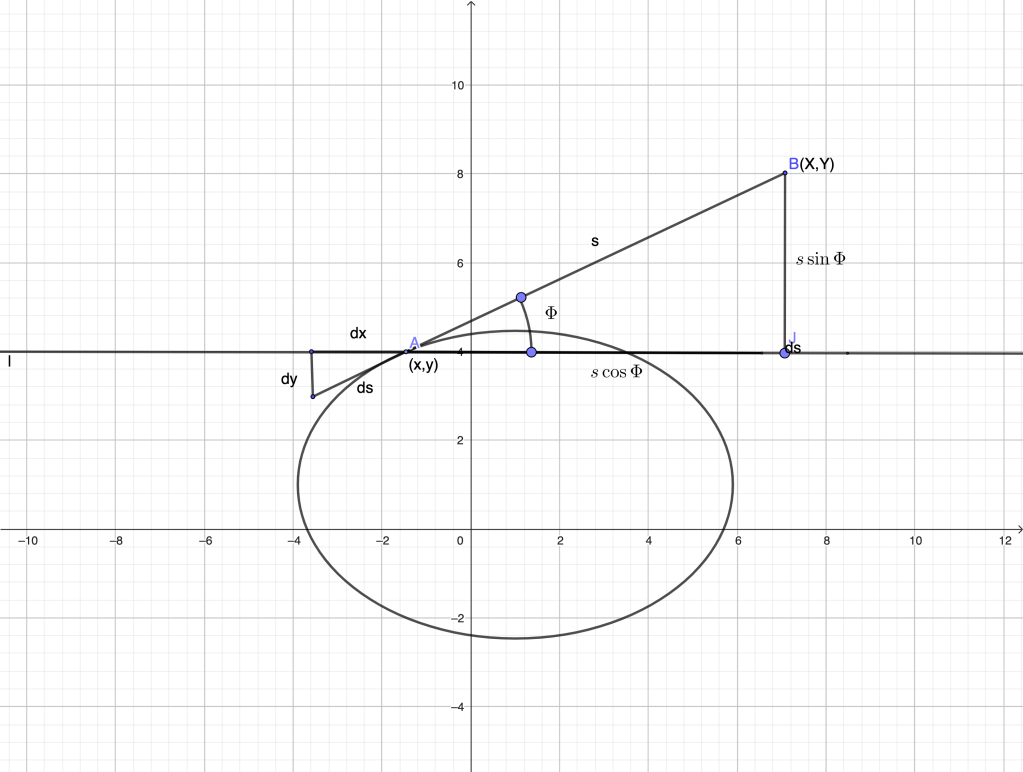

A related phenomenon: blow up in finite time.

Local solutions issued from can be extended to the boundary of

, but not necessarily in the

-direction. The reason is a fast (superlinear) grow of

as

, assuming that the domain of definition of

extends indefinitely in the

-direction. A simple example is the problem

,

whose explicit solution “blows up” as

, despite the fact that

is smooth on the whole plane. The role of the superlinear growth at infinity is similar to the role of Lipschitz (or Osgood) condition in bounded regions for uniqueness. The above problem is equivalent to

Convergence of the improper integral prevents

from attaining arbitrarily large values. Calling

, we have

. This phenomenon is called finite time blow-up and is exhibited by ODEs with superlinear right-hand-sides, by some evolution PDEs with superlinear sources, etc.

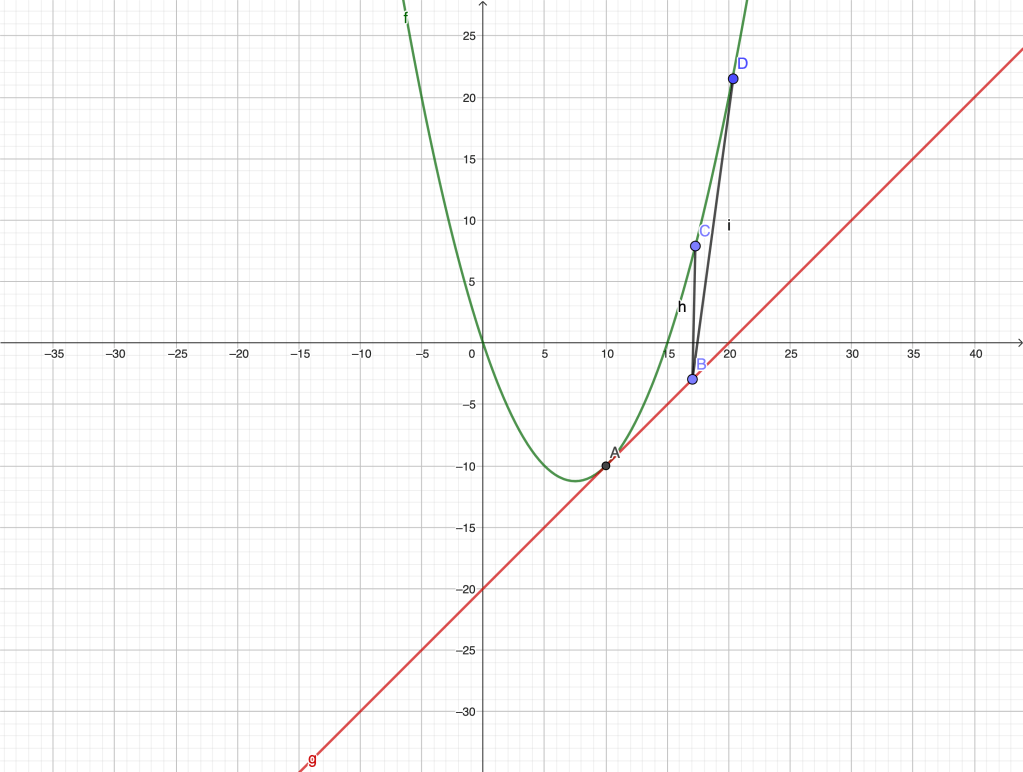

The same reasoning applies in the general case when there exists a continuous such that

as

(resp.

as

) if only

.

This time, under assumptions guaranteeing existence and uniqueness of solutions and provided the first condition above holds, the (forward) solution to with

stays to the left of the solution of

with . The latter blows up in finite time, namely at time

, forcing the solution to our IVP to blow up at some

.