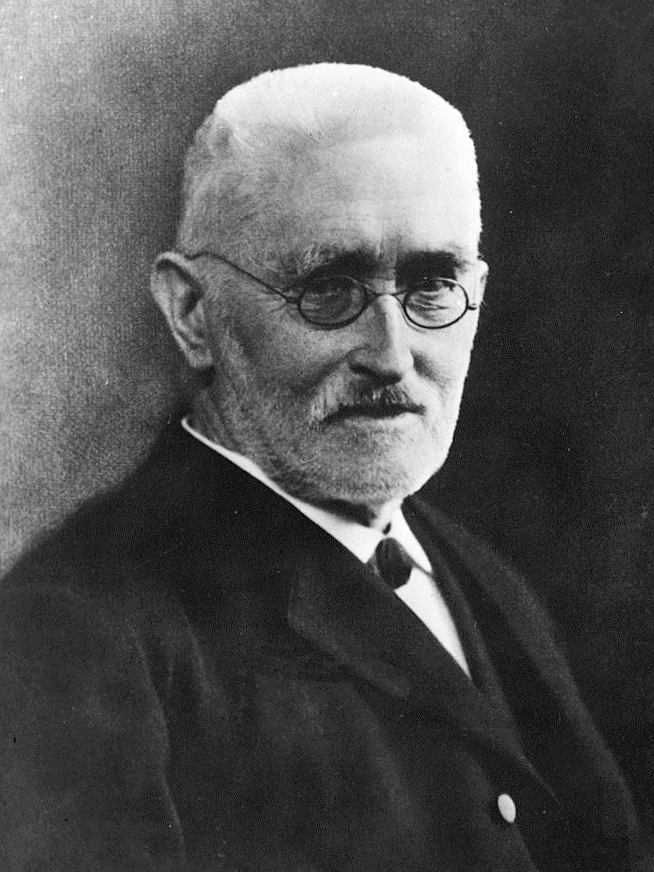

Main contributors to the theory of real numbers. From left to right: Eudoxus, S. Stevin, G. Cantor and R.Dedekind.

Nowadays students are exposed to the concept of “real line” as a model of the one-dimensional continuum in middle school. The real line contains all previously encountered classes of numbers: natural, integers, rational and irrational and no “gaps” are left. This object, so ubiquitous in modern mathematics, constitutes the basis upon which all of Calculus, Real and Complex Analysis and Linear Algebra (over or

) are built.

It may come as a surprise the fact that the concept crystallized relatively recently, after a slow and painful evolution of the concept of number over the centuries, with contributions from various civilizations shaping our current understanding.

In the Western hemisphere, as far as a systematic development is concerned, the story starts in ancient Greece around 500 BC. Greeks derived their Mathematics from older Egyptian and Babylonian traditions, which viewed Mathematics as a practical tool for counting and measuring.

According to Plato (Philebus 56D-57E, see [2]), there were two kinds of Mathematics in Greece, “that of the people and that of philosophers”. The mathematics of the people was called logistics (λογιστική) and followed the Egyptian/Babylonian tradition. It was concerned with calculations and measurement. That of philosophers, especially appreciated by Plato (429-348 BC) was viewed as a means for apprehending truth. Accordingly, they had a nuanced understanding of numbers. Only counting or natural numbers except for the number one were “numbers” in their own right for them. They used the term “arithmos” (ἀριθµός) for those numbers, and “arithmetic” (ἀριθμητική) for the related study. The reason why the unit was not considered a number was rather philosophical: the unit was a monad, related to the “essence” and indivisible, while a number, by definition, is a multitude of units. This ontological distinction is made by Aristotle in his Metaphysics, 1039a15 and elsewhere, and it is the historical reason why “one” was not considered a prime number. It was not a number at all!

Here is another nuance of Greek mathematics: they would carefully distinguish between numbers and magnitudes. Those belonged to completely different realms. Numbers were discrete whereas magnitudes were continuous. There were different kinds of magnitudes: lengths, areas, volumes, times, etc. When Greeks referred to a magnitude, they did not have a number in mind. A length was a portion of a line; an area was a portion of the plane. Their formulation of Pythagorean Theorem, for instance, involved squares built on the legs and the hypothenuse of a right triangle, and the proofs amounted to shape rearrangements.

Apart from “arithmos”, Greeks had the concept of “logos” (λόγος), which can be translated as “ratio”. These “fractions” were not actual numbers and served the purpose of attaching a “relative” size to magnitudes. According to Elements, Book V, Definitions 3 and 4, “a ratio is a sort of relation in respect of size between two magnitudes of the same kind”. However, it did not make sense for them to consider the ratio of a length to an area, or of length to time (mixed ratios). They only considered ratios of magnitudes of the same kind and ratios of numbers. Ratios could be compared between magnitudes of different kinds by means of proportions. Here is an example, [2]: “Triangles and parallelograms which are under the same height are to one another as their bases” (Elements, book VI).

Numbers can be added and subtracted, and so can magnitudes of the same kind, but ratios cannot. An abstract interpretation of the concept of ratio in Greek mathematics can be found in Bourbaki, [3]: “the ratios of integers are conceived by the classical Greek mathematicians as operators, defined on the set of integers or on a part of this set (the ratio of p to q is the operator which, to , makes correspond, if

is a multiple of

, the integer

, a multiple of

“.

Discovery of Incommensurability

A significant milestone in Greek mathematics was the discovery of incommensurability, traditionally attributed to the Pythagoreans. They found that some lengths, such as the diagonal of a square and its side, could not be “measured with a common unit”. In other words, there were not enough ratios of numbers to account for all possible ratios of magnitudes. According to Fowler [2], the discovery may be related to experimentation with anthyphairesis (the Euclidean algorithm/continued fractions) by noticing that in some cases the process continued indefinitely, and no common unit could be thus found. Anthyphairesis applied to the side and the diagonal of a square or to the side and the diagonal of a pentagon easily lead to a periodic continuous fraction and consequent incommensurability. Thus for example, the ratio of the diagonal of a square to its side (which we identify with the real number ) produces the continuous fraction

.

In many modern textbooks it is claimed that the Pythagoreans discovered that the number was irrational. Such claim is anachronistic and inaccurate; neither fractions or

were numbers at all.

Eudoxus’ Theory of Proportions

In response to the problem of incommensurability, Eudoxus, who lived in the third century BC and attended Plato’s Academy, developed the so called theory of proportions. Eudoxus’ theory, as rendered in Euclid’s Elements, provided a way to compare (homogeneous) magnitudes, narrowing the gap between arithmetic and geometry. Namely, “magnitudes are said to be in the same ratio, the first to the second and the third to the fourth, when, if any equimultiples whatever be taken of the first and third, and any equimultiples whatever of the second and fourth, the former equimultiples alike exceed, are alike equal to, or alike fall short of, the latter equimultiples respectively taken in corresponding order. When, of the equimultiples, the multiple of the first magnitude exceeds the multiple of the second, but the multiple of the third does not exceed the multiple of the fourth, then the first is said to have a greater ratio to the second than the third has to the fourth” (Elements, Book V, Def. 5). In other words, given four magnitudes we say that the first is to the second as the third is to the fourth,

if, for any integers

the following equivalencies hold

,

and similarly for the “less than” and the “greater than” relations between ratios. If two magnitudes and

are commensurable, there exist integers

and

such that the equality relation above holds. If they are incommensurable, the two extreme relations furnish “rational approximations” to the given ratio

. But again, neither those rational approximations or the final ratio were “numbers”.

The main advantage of Eudoxus’ theory was that it could be applied to both commensurable and incommensurable magnitudes, see Heath [1]. It foreshadows the construction of real numbers given by Dedekind over two millennia later.

Such was the official position of Greek mathematics, as portrayed in their most influential text, the Elements of Euclid, around 300 BC.

Logisticians, on the other hand, viewed fractions as numbers and freely added and subtracted them, specially fractions with numerator equal to one, following the Egyptian tradition.

The Hellenistic Period and Beyond

During the Hellenistic period, Greek Mathematics continued to build on the above concepts. Archimedes made significant contributions to the understanding of numbers and geometry, including the approximation of using the method of exhaustion that had been introduced by Eudoxus and related to the above rational approximations of the perimeter/radius ratio. Notably, Archimedes applied this method to the computation of areas of non-trivial shapes (parabolic sector, sector bounded by an arc of a spiral, etc.) Many applications of this method can be found in the Book XII of the Elements.

With the decline of Greek Mathematics in the third century AD, philosophical considerations gave way to a return of the naiver point of view of logisticians, [3]. A representative of that period is Diophantus of Alexandria, who was the first mathematician to recognize (positive) fractions as numbers. His main motivation came from Algebra, by accepting rational and even irrational numbers as possible values for coefficients and solutions to algebraic equations. Arithmetica is the major work of Diophantus and the most prominent work on premodern Algebra in Greek mathematics. Thus, a major advancement, namely the development of Algebra, was accompanied by a conceptual regress, [3].

Medieval Developments and Stevin’s Innovations

The medieval period saw a relative stagnation in the advancement of Mathematics in Europe, but significant progress was made in the Islamic world. Mathematicians like Al-Khwarizmi and Omar Khayyam expanded on Greek ideas and introduced algebraic methods that would later influence European mathematics. Among other things, negative numbers were introduced about 620 CE in the work of Brahmagupta (598 – 670) who used the ideas of ‘fortunes’ and ‘debts’ for positive and negative. By this time a system based on place-value was established in India, with zero being used in the Indian number system.

The Renaissance brought a resurgence of interest in mathematics in Europe. Arithmetica was first translated (never published) from Greek into Latin by R. Bombelli in 1570. Bombelli realized that, once a unit of length is chosen, there is a one-to-one correspondence between ratios and lengths. He thus had a geometric version of the real numbers. In his Algebra, he was the first European who clearly stated (and gave geometric proofs of) the rules for multiplication of positive and negative numbers: ,

etc. Bombelli is also responsible for an early use of “imaginary” numbers for the solution of cubic equations.

In the same century, Simon Stevin, a Flemish mathematician, adopting the point of view of Bombelli, made groundbreaking contributions by advocating for the use of decimal fractions. In his work De Thiende (The Tenth, published in 1585), Stevin demonstrated how fractions could be represented as decimal numbers, making calculations more straightforward and paving the way for the inclusion of irrational numbers in arithmetic. For the first time, the unit, fractions and irrational numbers were members of one and the same numerical field. In Stevin’s own words: “We conclude therefore that there are no absurd, irrational, irregular, inexplicable or deaf numbers; but that there is in them such excellence and agreement that we have subject matter for meditation night and day in their admirable perfection”.

Stevin’s work was crucial in transitioning from a purely geometric interpretation of numbers to a more algebraic and analytical approach. His decimal fractions also inspired Newton’s study of infinite series.

The real line

The first mention of the number line used for operation purposes is found in John Wallis’s (1616 – 1703) Treatise of Algebra. In his treatise, Wallis describes addition and subtraction on a number line in terms of moving forward and backward, under the metaphor of a person walking. The one-to-one correspondence between points on a line and numbers had been established.

René Descartes (1596 – 1650) took the idea further with his introduction of the Cartesian coordinate system on the plane and in space. In his work La Géométrie Descartes linked Algebra and Geometry, allowing geometric problems to be solved algebraically and viceversa. This unification laid the foundation for Analytic Geometry. The analytic study of curves gave rise to the birth of Calculus. The introduction of coordinates is essential to the construction of many physico-mathematical theories like Mechanics, Electromagnetic Theory, Thermodynamics, Statistical Mechanics, &c.

A rigorous construction

Stevin’s decimals did not lend themselves to a satisfactory construction of real numbers, in particular they did not provide sound definitions of the operations of sum and multiplication. The year 1872 saw the publication of work by G. Cantor and R. Dedekind, who independently provided a rigorous construction of real numbers out of rationals. Cantor’s construction is based on classes of equivalency of “Cauchy sequences” of rational numbers, whereas Dedekind’s approach hinges on the concept of “cut”, and is conceptually very close to Eudoxus’ theory of proportions. Both constructions were possible thanks to the recently developed language of the theory of sets, which allowed to consider sets of very large “size” (more precisely, cardinality). Such flexibility raised suspicion from many relevant scholars and a decades long debate ensued. Although the construction of reals by Cantor and Dedekind have been largely accepted and is regularly taught at colleges and universities, alternative schools of thought including Intuitionism and Finitism are still in existence and have developed their own Mathematics based on restricted versions of Set Theory, restricted Logic, etc.

Beyond the reals

We should also mention that alternative constructions of the continuum, built upon standard Set Theory, have been proposed starting in the last decade of the XIXth century. A full reconstruction of Analysis was proposed in the 1960s by A. Robinson, culminating with his Nonstandard Analysis, published in 1966. In his work, the real line is replaced by a non-Archimedean”hyperreal” one, containing actual infinitesimals and infinities of different orders along with ordinary real numbers. The main goal was to remove the concept of limit and construct a purely “algebraic” version of Analysis, thus vindicating the dream of Leibniz. But this is a major and intricate topic that deserves a separate post.

References

[1] Sir T. Heath, “A History of Greek Mathematics”, Oxford Clarendon Press, 1921.

[2] D.H. Fowler, “Ratio in Early Greek Mathematics”, Bulletin of the AMS, Vol 1 (6), 1979.

[3] N. Bourbaki, “Elements of the History of Mathematics”, Springer, 1999.