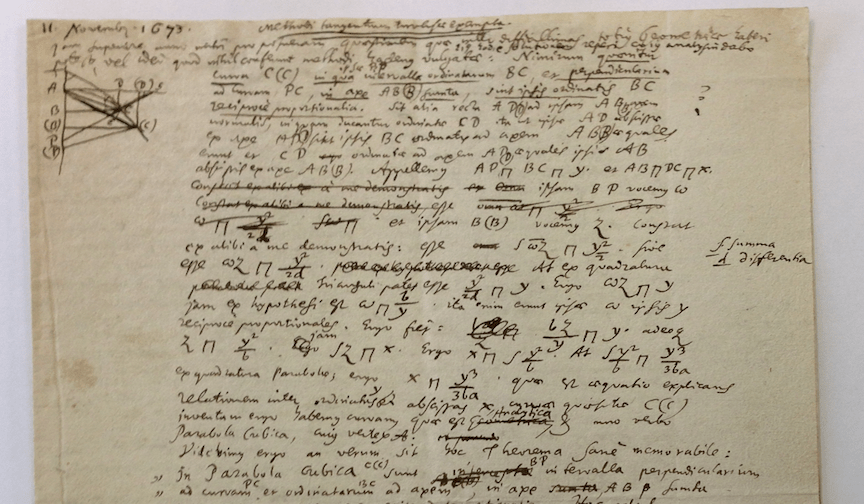

In pre-epsilontic times, mathematicians understood definite integrals as continuous sums of infinitesimals (in the above image, a page from Leibniz where he introduces the signs for difference and

for sums. He uses the sign

for adequalities). In the hands of the Bernoullis, Huygens, Euler, Lagrange, Legendre and many others, Infinitesimal Calculus, including the theory of differential equations as well as numerous applications to Mechanics, Optics, etc. developed for over 150 years under that conceptual framework. The situation changed during the second half of the XIX century, when set theory and a rigorous construction of the continuum was put forward by Cantor and Dedekind. Supposedly, they provided a final answer to the nature of the continuum that has been prevalent for over 150 years by now. Such a sparse ontology did not convince everyone, and there have been numerous alternative models of the continuum developed over time, aimed at restoring the language of infinitesimals, see [1]. As for the concepts of derivative and integral, infinitesimal interpretations were replaced by epsilons and deltas at the hands of Bolzano, Cauchy and, notably, Weierstrass.

Let us recall the definitions for the sake of completeness. For a real function of a real variable , if

is a point in the closure of

, we say that

if for any

there exists some

such that

Both derivatives and integrals are limits. The derivative of at a point

in the interior of

is the limit

whenever the latter is finite. In the case of the definite integral over , we consider partitions

, where

with tags

and form the Riemann sums

.

If the above sums have a finite limit as

(uniformly w.r.t. the partitions and the tags), we say that

is Riemann-integrable with integral equal to

. Back to the language of epsilons and deltas, we are requiring that for any

there exists

such that

I am not concerned here with the alternative constructions of the continuum and the non-standard approach. My main concern is the teaching of (standard) Calculus. It is my belief that the main difficulties encountered by students when faced with the above definitions are philosophical/psychological in nature, as they feel a disconnection with good old Algebra and finite procedures. In order to fill the gap, I believe that the language of infinitesimals is to be preferred, specially in introductory courses. As I pointed out elsewhere, this is the language used by most users of Calculus, including Physicists and Engineers. Just like derivatives are quotients of infinitesimals, integrals are sums of infinitesimals, thus revealing a common theme. In other words, I believe that Calculus should be presented as an algebra of infinitesimals.

The main objection to this approach is the fact that infinitesimals cannot be properly defined in the realm of standard Calculus, based on the standard real line. I believe however that the pedagogical advantages stemming from its more intuitive character and its agreement with the historical evolution of the subject is worth the lack of rigor on a first acquaintance with the subject.

Let’s consider the different types of sums used in Calculus.

Adding two numbers is an operation everyone is familiar with. The (inductive) extension to a finite amount of addends is trivial, thanks to associativity. Here we are in the realm of Algebra.

Things become trickier when we intend to add infinitely many numbers. We already encounter this situation In Zeno’s paradoxes: In order to travel a certain distance, say , one has to travel half of the distance, then a fourth of the distance, then an eight of it, etc. Zeno rejected the possibility of such process made of infinitely many steps since, in his opinion, it could never be completed. Thus for Zeno and the followers of Parmenides, motion did not exist. Greek mathematics rejected completed infinite processes in general (see [2]) and therefore could not attach a numerical value to the “infinite sum”

Standard modern mathematics, however, has embraced the idea of the continuum through the concept of real number, originated with Simon Stevin and his decimal representations. Thanks to a hypostatic abstraction, now we declare numbers (real numbers) a certain property of sequences of rational numbers. In simpler terms, we adjoin to the number system all potential “limits”. Such construction would have abhorred Eudoxus and Euclid, but Cantor and Dedekind, along with most current mathematicians, were perfectly comfortable with it. In order to circumvent Zeno’s paradox, we start by defining the concept of infinite sum. The simplest choice, as is well known, is to consider “partial sums”

which in this case can be easily computed in closed form, , and then noticing that

“stabilizes towards

“, and thus has the real number

as its limit, according to the standard paradigm. In modern terminology, we would say that we are dealing with a convergent series, whose sum is

.

Several comments are in order. we are free to choose what we mean by an infinite sum, as the concept cannot be reduced to that of a finite sum. There are other choices (Cesaro’s convergence, for example) ;

this mathematical construction does not solve the paradox, which belongs in the realm of metaphysics;

in this example, the sum happens to be a rational number, but the concept of real number allows to attach a sum to series like

which is the “irrational” number .

A necessary condition for the series to have a finite sum in the above sense is that the general term of the sequence converge to zero,

. Indeed, if

stabilizes, the difference

has to vanish asymptotically. The elementary theory of numerical series shows that this condition is not sufficient and that there are two main mechanisms of convergence:

the general term converges to zero fast enough and

the series contains infinitely many positive and negative terms and cancellations occur.

As an example of the first mechanism, any series of geometrically decreasing terms like the one above is convergent. Also, any series whose terms behave asymptotically as those of a convergent geometric series is convergent (this is called the ratio test). A relevant example of cancellation is given by Leibniz’s series above, where the partial sums oscillate around

.

Summing up, for a sum over a discrete set of indices to be finite, the terms have to become small in a way that balances the number of addends, stabilizing the partial sums towards a finite limit.

Definite integrals showcase the next level of summation. In Riemann’s construction with uniform partitions, generic terms of the Riemann sums are of the order of , thus balancing the number of addends

. In contrast with series, in this case

the terms become arbitrarily small simultaneously, allowing for a “larger” number of addends, namely the continuous sum

over the set of indices . We can think of

as the infinitesimal addends making up the sum. The situation here is more delicate, since all the terms making up the Riemann sums change every time and the values of the sums may not stabilize if the function is too discontinuous. Everything works nicely for continuous functions though.

When a Physicist needs to find the total mass of a non-homogeneous bar with density , he/she reasons as follows: choose an infinitesimal portion of the bar of length

between two infinitesimally close points

and

. Being infinitesimal, the density is constant and equal to

on that portion and the corresponding mass is

. The total mass is thus the sum of the infinitesimal masses

.

Physics and Engineering books contain plenty of such formulas to compute extensive magnitudes. Yet the way Calculus is currently taught is at odds with the above line of thought. A colleague engineer once told me “I had to relearn Calculus. The version mathematicians taught me was useless”.

The balance between the cardinality of the set of indices and the size of the terms is critical. For instance, if we consider “Riemann sums” of either form

the corresponding limits are trivial,

for “reasonable” (say, continuous on ) functions. Indeed, in the first case the addends are too small, while they are too big in the second one:

as

.

We can further consider sums over a doubly continuous set of indices . Those are double integrals

,

where the addends are quadratic infinitesimals with respect to

and

. The same applies to general multiple integrals. Unbalanced Riemann sums give rise to trivial objects like

,

etc.

I believe formulas like provide deeper insight than all the technicalities related to the

definition of the definite integral. They help understand why the concept of definite integral is relevant as it strikes the sweet spot where the “number of addends” (i.e. the cardinality of the set of indices) and their size balance each other, resulting in convergence to a finite, nontrivial sum.

References:

[1] “Ten misconceptions from the history of Analysis and their debunking”, P. Blaszczyk, M.G. Katz and D. Sherry, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1202.4153.pdf

[2] “Elements of the history of Mathematics”, N. Bourbaki, Springer Science & Business Media, 1998.