Before we move onto concrete examples, let us quickly review some basic differentiation rules. In order to differentiate equations of the form

we need to replace all the variables by their perturbed values

and disregard infinitesimals which are of order higher than one with respect to

in the resulting expression.

For example, if for some constants

, we have

,

since . In this case, the expression is linear in

and

and, therefore

.

To differentiate an equation involving a product, , we notice that

and, since , we get

.

Let us next find for

Now, we observe that

,

Hence, up to linear terms,

and therefore

,

where we have disregarded the quadratic term . Finally, since

we get

.

Successive applications of the product rule give the important power rule:

and, in general, . For negative integer powers the same rule applies, as follows from the quotient and power rules. Combining the previous, we can differentiate any equation involving polynomial or rational functions.

What about irrational/transcendental functions? As for -th roots, we have

by just rearranging the power rule. Therefore, the power rule extends to rational powers.

Let’s move now to the fun part.

Reasoning with infinitesimals

Suppose we want to compute . In modern textbooks, they focus on the derivative

. The computation goes more or less like this.

,

where the trigonometric identity for the difference of sines has been used, as well as the fact that as

. All this is nice and clean but does not provide compelling intuition. Next, we provide a proof based on infinitesimals. No computation needed. It is essentially a picture-based proof.

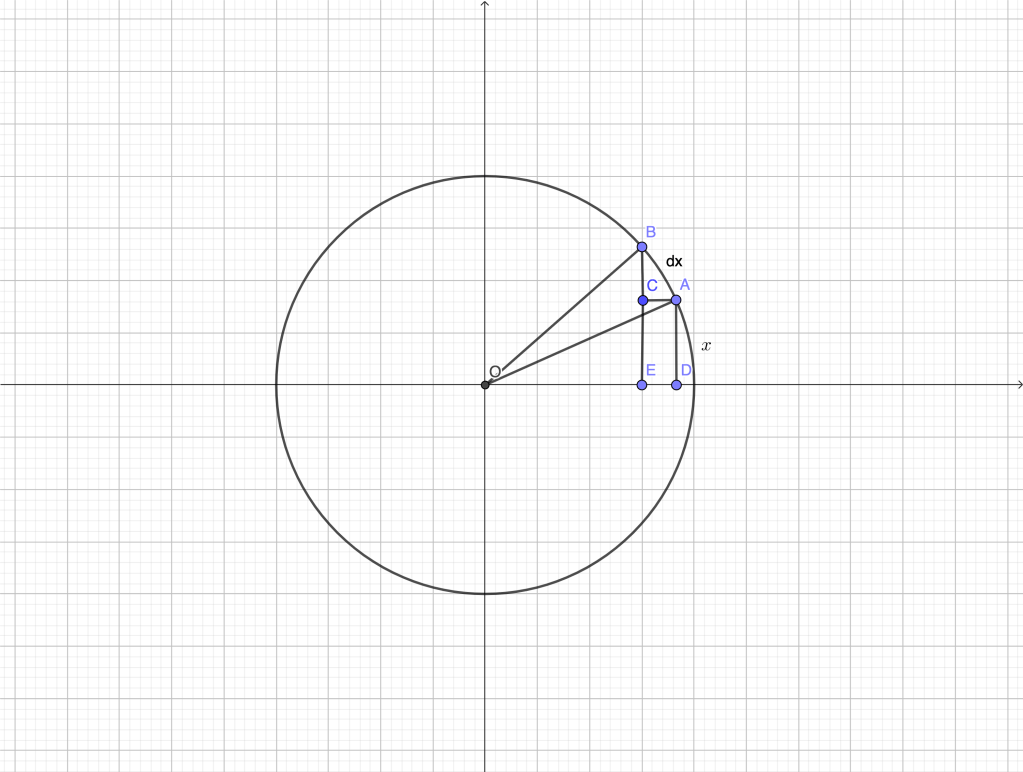

In the figure below, the unit circle is represented, and we consider a generic angle being increased by an infinitesimal amount

.

The corresponding change of is

. The triangles

and

are similar since they are right and

. Therefore,

.

From the perspective of rigor, the above argument is flawed, for many reasons. The “triangle” is not really a rectilinear triangle,

is actually

, etc. BUT it provides a visual, compelling reason as to why

and the conclusion is absolutely correct. It is correct because we know that the vanishing circular arc

is indistinguishable from its tangent, while

is indistinguishable from

.

Admittedly, this type of argument relies on the ability to recognize which approximations will become exact in the limit. We believe this is a skill worth developing.

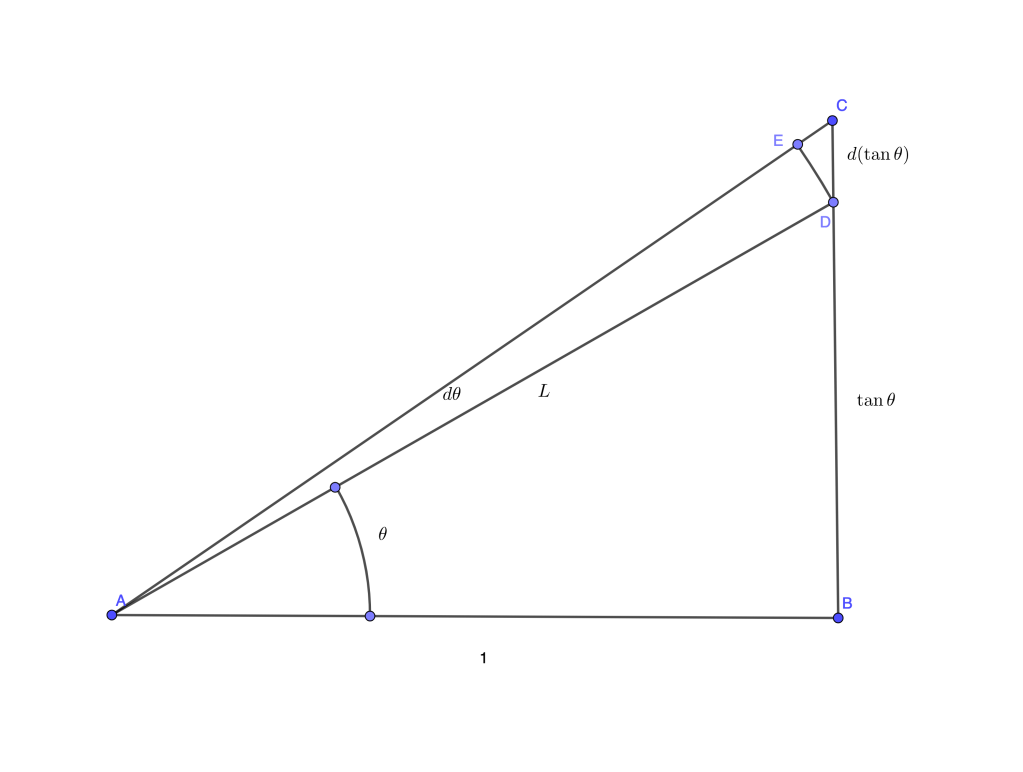

Here is another example mentioned in the beautiful book [1] and attributed there to Newton. Let us show that . In the figure below,

and

is right. Then

. We increase the angle

by an infinitesimal amount

. The tangent is then increased by

. Let

be the arc of a circle centered at

.

The triangles and

are similar and thus

or

(because differs from

by an infinitesimal) and finally

.

Solving problems using differentials

Let’s start with a simple optimization problem which is more elegantly solved using differentials.

Consider a sliding segment of length , with endpoints on the positive

and

semi-axes. What is the location of the segment for which the area of the triangle that it determines on the first quadrant is maximal?

The standard approach to the problem is to express the area of the triangle as a function of some parameter (the horizontal projection of the segment, some angle, etc.) and find the value of the parameter that makes the derivative equal to zero. A more “symmetric” approach would be as follows. Let and

be the lengths of the legs of the triangle. Then,

Differentiating both relations,

A necessary condition for to reach a local maximum is

. Thus we get a system of equations

For the above homogeneous linear system to have a non-trivial solution (so infinitesimal changes are allowed) we need zero determinant,

which in our case implies

and then, from our second finite relation we get

.

If we were to follow the approach based on derivatives, we could either express and substitute, leading to the problem of minimizing a function of

We would then find and set it equal to zero. In this simple example there is no big difference, but notice that with our approach: a) no “independent variable” is singled out; b) we avoid the annoyance of taking the derivative of a square root; c)

does not appear explicitly throughout the manipulation with differentials, but only at the beginning and at the end, when we appeal to finite relations (and this is, in principle, unavoidable given the nature of differential relations).

A similar example is presented in [2]. There, the classical problem of minimizing the length of a piece-wise straight path connecting two given points with a given line (so called Heron’s problem) is solved.

The given quantities (see Fig. above) are ,

and

and the quantity to minimize is

. This problem involves more parameters and, no matter what quantity you choose as independent, the solution using derivatives is a bit messy. Using differentials, it reduces to a compatibility condition for a homogeneous linear system as above. Namely, we have

.

Differentiating all the equations gives

The condition of extremum is . Replacing

and

in terms of

and

we end up with a

system for

:

The determinant should be zero, that is . This in turn implies

and, consequently, . Finally,

.

Observe in particular that so the path should “reflect” on the line.

In both examples above, we solved a conditional optimization problem. A possible approach is to use the method of Lagrange multipliers. Thus in our case we are trying to. minimize

under the constraint

.

The main advantage of that method is to keep the symmetry between the variables, at the expense of introducing a number of multipliers. On our next post, we will discuss how the method was introduced by Lagrange to deal with constraints in mechanical systems. Not surprisingly, infinitesimals were at the heart of his analysis, in the form of virtual displacements.

References:

[1] T. Needham, “Visual Complex Analysis”, Oxford University Press, 1999.

[2] T. Dray, Corinne A. Manogue, “Putting Differentials Back into Calculus”, The College Mathematics Journal 42 (2), 2010.