Nowadays, we conceive Calculus as the study of functions. The concept of function, originated with Leibniz, was not defined in its full generality until the mid 1800s by Dirichlet. But in the early development of Calculus, the main objects of Calculus were variable quantities, notably those that varied together. For example, Euler considered quantities that vanish or increase infinitely in his famous Introductio in analysin infinitorum, from 1748. Such dynamic view of quantities is one of the features that have been lost or, at least obscured by the modern approach, based on limits. The definition is a bit too “algebraic” and static: the dynamics is encoded in the conditional “

such that..” Euler’s “quantities”, in contrast, had a variable nature.

A quantity that we can consider as becoming ever smaller is called an infinitesimal. A possible mental image is that of a segment which increasingly diminishes until it becomes a single point, or an angle whose sides become closer and closer until they coincide. In modern terminology, an infinitesimal is a variable whose limit is zero. If a variable quantity is approaching some (finite) value

, the difference

is an infinitesimal.

Calculus is concerned with simultaneous variations of related quantities. Thus for example we can consider the variation of the area of a square of side when its side is increased/decreased by an infinitesimal amount. Such infinitesimal amount was denoted by Leibniz, the Bernoullis, Euler, etc. and even today by physicist, engineers, etc, by

, and is called a differential. A simple computation gives the new area

The corresponding change of area is , which is another infinitesimal. In modern terminology, we say that the area is a continuous function of the side: if the side is infinitesimally increased/decreased, the area changes infinitesimally. In most applications to Physics and Engineering, we deal with continuous functions.

A central idea to Calculus is that infinitesimals can be classified according to the relative speed with which they approach zero. It does not make sense to talk about the speed of one infinitesimal, but it does make sense to talk about whether two related infinitesimals (as the ones considered above) approach zero at a comparable speed. Thus if is an infinitesimal quantity, the related infinitesimal

approaches zero much faster, since their ratio

is itself infinitesimal. We all know that if we look at a sequence of values like

, their squares form a sequence that approaches zero much faster;

. The infinitesimal

approaches zero even faster since the ratio

is again an infinitesimal.

These considerations lead to the concept of order of infinitesimals. Namely, given two related infinitesimals and

, we say that

is of a higher order (than

) if their ratio

is infinitesimal. A nice notation introduced by E. Landau and widely used in Computer Science is that of “little o”. Using the “little o” notation, we write

In modern terminology, we would say: given two functions and

with

, we say that

if

. This is nice and clean, but one has the impression that the dynamics is somehow lost.

In many instances, two related infinitesimals are “comparable”. Back to the previous example of the area as a function of the side, the quotient

is not an infinitesimal, but takes values closer and closer to instead. In such cases we use the “big O” notation. For generic related infinitesimals

and

as above, we would write

Thus, .

In the particular case when the ratio approaches , we say that the infinitesimals are equivalent. That means, of course, the given infinitesimals take very close values as they vanish. Equivalency is denotes by the symbol “

“

It seems to me that the qualitative aspect of the concept of order is not sufficiently stressed. Even the suggestive “little o” notation is not used in many of the standard current undergraduate Calculus textbooks, including J. Stewart’s, Edwards & Penney, Larson & Edwards, and many others. I think this is very unfortunate, and is part of a general tendency to avoid “qualitative” and “synthetic” reasoning, favoring quantitave and procedural aspects instead.

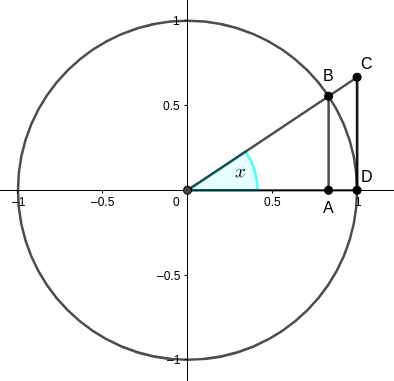

An interesting infinitesimal is , where

is an infinitesimal angle. In the figure below, the radius is chosen to be one for simplicity. The following inequalities are obvious.

or, equivalently,

which, after dividing by throughout, becomes

,

the latter equality being a consequence of similarity of triangles and

.

Clearly, as approaches zero,

approaches one. As a consequence. The ratio

, being trapped between two quantities approaching one, also approaches one. Using the above terminology,

and

are equivalent infinitesimals,

. In the language of limits

.

A vivid example of infinitesimals of different orders is given by the different segments, areas, etc. determined on a circle by an infinitesimal angle .

When the angle is infinitesimal, the following quantities (functions of the angle):

and the area of the yellow circular segment are related infinitesimals.

is just a linear function of

so

which is a non-zero constant. Therefore

. Next, we see that

which, according to the previous example, is equivalent to

. Therefore,

. As for

, we have

.

Since ,

and

.

Finally, the area of the segment is

On the right hand side, we have the difference between two equivalent infinitesimals. What is the order of that? I will leave the question open at this point, and will come back to it in my next post, where we will deal with successive differences and differentials.